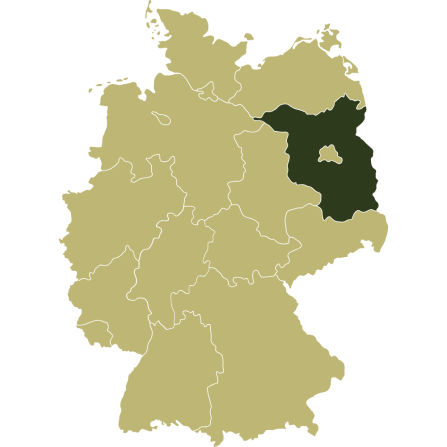

Municipalities

Geographical size

Human population

Number of livestock farmers

Livestock farming systems

Large carnivore species

Wolf population

SOCIOECONOMIC CONTEXT

Brandenburg is characterised by its largely rural landscape, dotted with numerous small towns and only a few high-density urban centres. The GDP per capita (in purchasing power standards, PPS) stands at 98.3% of the EU-27 average, which places it below the German national average of 118%. In 2023, the employment rate was 56.1%, also lower than the national average. Additionally, the population is aging.

The degree of industrialisation is low compared to other German regions, yet Brandenburg benefits from its adjacency to Berlin. Commuter flows and spill-over effects in industries, including logistics, engineering, and chemicals, are particularly notable in areas close to the capital.

There is an ongoing structural transition and investment directed towards cleaner, more knowledge-intensive industries. This represents a shift away from traditional heavy industries and coal, especially in the region Lusatia, which is also an important area for wolves.

Brandenburg is known for its well-preserved natural environment and its ambitious natural protection policies, which began in the 1990s. 15 large, protected areas were designated following Germany's reunification. Tourism is an important sector.

FARMING CONTEXT

Poor soils across most of Brandenburg, in combination with low precipitation (averaging 550 mm per year, with a declining trend due to climate change), provide less advantageous conditions for crop production compared to other German regions. However, farm and field structures are rather large, with an average farm size of 245 ha, a relic of former socialist production units and land consolidation, which provides economies of scale.

Livestock husbandry, particularly of bovines, equines and sheep, forms an important component of the regional farm structure. The most important farm types are specialist grazing livestock farms (37.8%), specialist field crop farms (36.9%), and mixed farms (20.7%). However, lack of profitability, and altered marketing and consumption patterns since Germany’s reunification in 1990, have caused a considerable decrease in livestock numbers, particularly bovines. Livestock numbers are now at levels similar to those of 1946, directly after World War II, with an average ruminant livestock density of 0.3 units per ha. The observed decline of grazing livestock threatens the maintenance of extensive grasslands and their associated biodiversity.

Main Challenges:

Soil & climate limitations, risk from extreme weather events.

Water scarcity and irrigation limits.

Digitalisation and investment barriers, alongside market and price pressures.

Wildlife damages, wolves, and livestock protection on ruminant livestock farms.

LOCAL CONFLICT ASSOCIATED WITH LARGE CARNIVORES

Until the Middle Ages, Brandeburg’s wolf population was large and stable. However, organised wolf eradication programs led to their local extinction by the end of the 18th century.

Since Germany’s reunification, wolves have been legally protected. The first territorial wolves returned to Brandenburg in 2007, and the population has since grown rapidly. As wolf numbers increased, so did livestock depredation events. In response, state authorities initiated systematic monitoring of these events and provided funding for damage compensation and livestock protection measures, including fencing, livestock guarding dogs and operating costs. In 2020, Germany spent € 9.5 million on herd protection and € 0.8 million on compensation payments.

The increase in depredation events poses new challenges for pastoralism in Brandenburg, particularly for shepherds and suckler cow holders. This potentially undermines political objectives linked to the support and expansion of grazing-based livestock systems.

Number of attacks:

Between 2007 and 2024, 2,357 livestock depredation events were reported, resulting in 7,920 animals killed through confirmed wolf attacks, 83% of which were sheep.

Social conflict:

Farmers and livestock holders suffer from wolf attacks, losing animals (sheep, goats, calves) and experiencing damage. They demand stronger preventive measures and sometimes the right to remove problem wolves.

Conservationists and nature protection groups generally oppose broad culling quotas, and emphasise non-lethal methods: prevention, compensation, legal protection of wolves.

The financial and labour burden of preventive measures such as fencing and guardian dogs, falls on the farmers. Many argue that the state support is insufficient, or overly bureaucratic.

Disputes exist over the speed and fairness of compensation payments, as well as over the conditions under which they are granted (e.g. minimum protection standards).

Public tensions are amplified through protests (e.g., “wolf watches”), campaigns, media framing, with some speaking of “wolf romanticism”, others of warning of a “wolf threat”.

Funded by the European Union. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or the European Research Executive Agency. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.